Understanding Your Trauma Responses

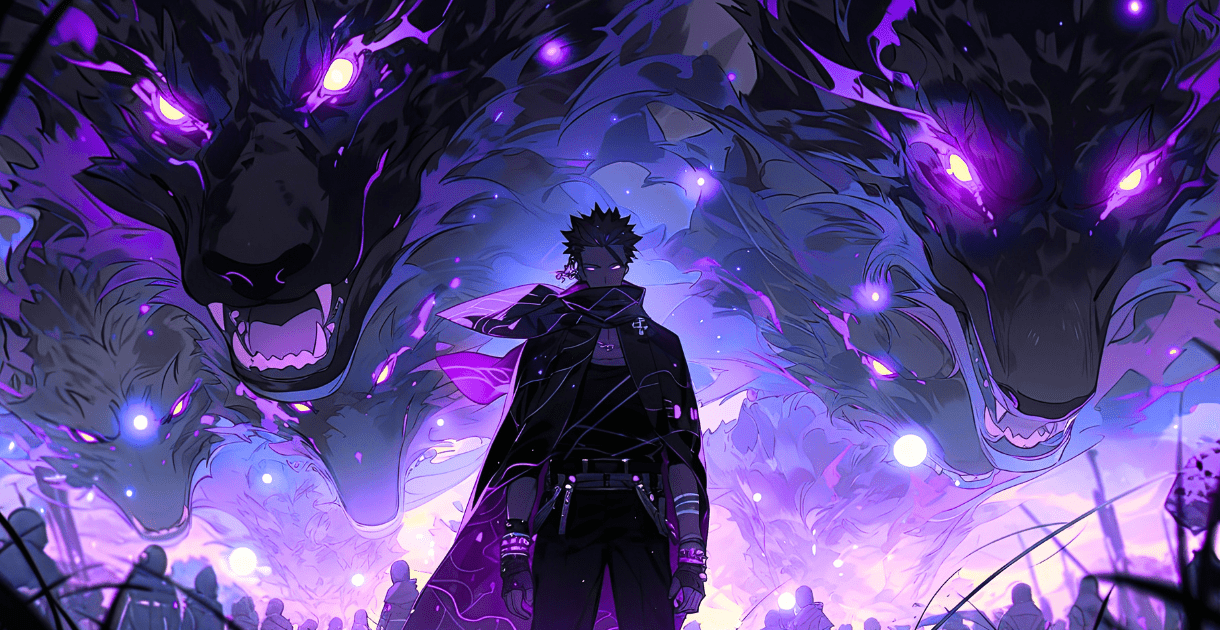

Most people have heard of the ‘fight or flight’ response when facing a threat, whether real or perceived. This article will talk about what happens inside the body when this automatic reaction is triggered. It is important to remember that the fight or flight response is an automatic physiological reaction to an event that is perceived as stressful or frightening.

The perception of threat activates the sympathetic nervous system and triggers an acute stress response that prepares the body to fight or flee. These responses are evolutionary adaptations to increase chances of survival in threatening situations. Overly frequent, intense, or inappropriate activation of the fight or flight response is implicated in a range of clinical conditions including most anxiety disorders. A helpful part of treatment for anxiety is an improved understanding of the purpose and function of the fight or flight response. This information handout describes what happens in the body physically when the the fight or flight response is triggered.

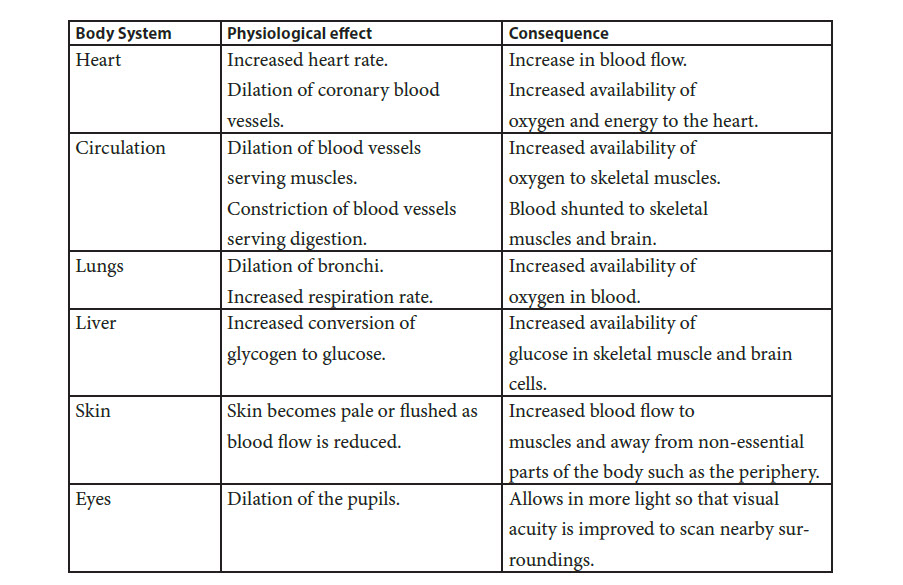

Physiological Responses

The fight or flight reaction is associated with activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The chain reaction brought about by the fight or flight response can result in the following physical effects:

In addition to physiological reactions there is also a psychological component to fight or flight response. Automatic reactions include a quickening of thought and an attentional focus on salient targets such as the source of the threat and potential avenues for escape. Secondary psychological responses can include appraisals about the meaning of the body reactions.

For example, patients with panic disorder often misinterpret fight or flight responses as signs of impending catastrophe (“I’m having a heart attack”, “If this carries on I’ll go crazy”).

History of the Fight or Flight Response

The fight or flight response was originally described by American physiologist Walter Bradford Cannon in the book Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage (1915). He noted that when animals were threatened, by exposure to a predator for example, their bodies released the hormone adrenaline / epinephrine which would lead to a series of bodily changes including increased heart rate and respiration. The consequences of these changes are increases in the flow of oxygen and energy to the muscles. Canon’s interpretation of this data was that there were emergency functions of these changes. He noted that they happened automatically and they served the function of helping the animal to survive threatening situations by readying the body for fighting or running.

A more modern understanding of the fight or flight response is reflected in the work of Schauer & Elbert (2010). Their more elaborated model of physiological / psychological / behavioral responses to threat is termed the ‘defense cascade’. They describe a series of stages which individuals exposed to threat or trauma may go through, including: freeze, flight, fight, fright, flag, fawn, and faint.

Why the Fight or Flight Response is Important

The physiological responses associated with fight or flight can play a critical role in surviving truly threatening situations. However, many people suffering from anxiety disorders or other conditions may have threat systems which have become over-active, or which are insufficiently counterbalanced by activity in the parasympathetic nervous system.

Many who suffer from anxiety will benefit from a deeper understanding of the fight or flight response. For example, those with panic attacks or panic disorder often misinterpret the bodily signs associated with fight or flight as signs of impending catastrophe and understanding the fight or flight response is therefore a helpful ‘decatastrophizing’ technique. Similarly, patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD or cPTSD) may mistake the increased physiological arousal as an indicator that there is a genuine threat present. Understanding more about the fight or flight response can help them to feel safer, and to implement relaxation and grounding strategies.

Beyond ‘Fight or Flight’

Research over the past few decades has identified up to 6 common types of trauma responses. While ‘fight or flight’ is the most talked about, there are four more that are as equally important to understand.

Freeze: The freeze response involves feeling paralyzed or unable to move or speak in response to the traumatic event. This may involve feeling frozen or numb, or experiencing a dissociative response.

Fawn: The fawn response involves attempting to please or appease others in order to avoid conflict or harm. This may involve sacrificing one’s own needs or wants in order to avoid upsetting others.

Flirt: The flirt response involves using charm, charisma, or sexuality to distract from or cope with the traumatic event. This may involve engaging in promiscuous behavior or using humor to deflect from the trauma.

Fidget: The fidget response involves engaging in repetitive or distracting behaviors in order to cope with the traumatic event. This may involve pacing, nail-biting, or other forms of physical restlessness.

By analyzing my past abusive relationships, I discovered that my common trauma responses are Fawn and Flirt. I used these almost exclusively to try to manage the volatile emotions of my exes. It often worked short-term and was a direct by-product of my childhood coping mechanisms where I often was the mediator between my parents fighting.

It has taken years to unlearn this automatic behavior, but learning mindfulness techniques and practicing CBT exercises has helped me to retrain my brain where I can choose to be mindful instead of reactionary when I am triggered.

No matter your go-to trauma response, you CAN learn how to unravel the automatic responses in your life and take back control of your emotions. Need help? Book a free 30-minute discovery call!

Download Your Free Worksheet

Download this free printable/fillable worksheet to understand what happens in the body during a trauma response.